How 300 children lost their fathers to lynching on a single day because of a conspiracy theory

OPINIONALAN BEAN | Baptist Global News DECEMBER 4, 2020

At last count, 73,923,495 Americans have voted for Donald Trump. Trump eclipsed Barack Obama’s previous record by more than 4.5 million votes. Trump topped his own 2016 performance by 11 million votes. That’s huge.

Trump lost the election; but he grew his base. By a lot.

That is not to say that everyone who voted for Trump is enthusiastic about family separation, the denigration of Black Lives Matter protestors, a tendency to value blind loyalty over competence, the president’s cozy relations with autocrats like Vladimir Putin, or a continual flow of strategic disinformation.

Some are willing to overlook these peccadillos because, they believe, Trump ushered in a booming economy and low taxes.

But Trump’s most avid supporters embrace his personality, posturing and policies with open arms because they live in an alternative universe. QAnon enthusiasts, for instance, believe their president Trump is secretly combatting a global cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles with a shared passion for ritual baby sacrifice. It is this battle, not the faux conflict between Republicans and Democrats, that will determine the future of the Republic. QAnon devotees anticipate a coming “storm” when Trump will round up, imprison and expose the enemies of America.

Millions of voters have never heard of QAnon yet are nonetheless convinced that George Soros secretly controls Washington politics, or that the COVID-19 pandemic is a liberal hoax. Ask these people if Barack Obama is an American citizen, or even a Christian, and you will typically hear an emphatic “no.”

“Only 3% of Trump voters believe Joe Biden won the election. That is stunning!”

Sidney Powell, one of the attorneys making allegations of massive voter fraud, is convinced that “communist money” and a sinister computer algorithm have combined to steal the 2020 presidential election. Powell’s legal claims may be failing miserably in the courts, but they are welcomed as gospel in the QAnon community.

According to a recent poll, only 3% of Trump voters believe Joe Biden won the election. That is stunning!

Nothing new about conspiracy theories

There is nothing new about conspiracy theories. Recently, while doing some research on the history of lynching, I learned that Anthony Bewley, a Methodist minister, was lynched in Fort Worth, Texas, back in 1860. Bewley was the victim of a bizarre conspiracy theory.

Bewley’s troubles began back in 1844 when the Methodist Episcopal Church divided over the issue of slavery. A resolution passed by the Southern churches explained that, “We regard the officious and unwarranted interference of the Northern portion of the Church with the subject of slavery alone, a sufficient cause for a division of our Church.”

Bewley’s troubles began back in 1844 when the Methodist Episcopal Church divided over the issue of slavery. A resolution passed by the Southern churches explained that, “We regard the officious and unwarranted interference of the Northern portion of the Church with the subject of slavery alone, a sufficient cause for a division of our Church.”

Bewley’s presence in North Texas was deeply resented by Southern Methodists. Texas was a slave state, after all, and Bewley was affiliated with the abolitionist Northern Methodists. Bewley was a circuit preacher ministering to 232 people in six sparsely populated counties. He generally avoided the hot topic of slavery, but everyone knew where he stood.

In 1860, the year Bewley was lynched, two-thirds of Texas residents were from somewhere else. Many were from free states, and pro-Union sentiment was strong. A year earlier, Sam Houston, running on a Unionist platform, had been elected governor. Having brought Texas into the Union in 1846 (two years after the Methodist split), Houston regarded talk of a Southern Confederacy with suspicion. In this political environment, Bewley’s abolitionist sentiments were tolerated.

When the tide turned

But when John Brown raided Harper’s Ferry, and the Republicans selected Abraham Lincoln as their presidential nominee, the tide began to turn. Bewley knew he was living in a different world when he learned that Solomon McKinney and Parson Blount, two itinerant preachers from Iowa, had been run out of Dallas (and the state of Texas) for airing their anti-slavery views.

Bewley’s fledgling band of Methodist churches held their annual conference in Fannin County in July 1860. Attendees sensed something was afoot when two Southern Methodist ministers joined the gathering.

One of these visitors reported to the local “committee of vigilance” that a member of Bewley’s group had “sought to influence a local Negro by reading to him after which the slave became useless to his owner.” In his testimony before the committee, the man “apologized for incriminating any white man, even a suspected abolitionist, by the testimony of this Negro.”

Bewley and his followers were commanded to discontinue their activities forthwith. As the situation deteriorated, Bewley gathered his family and fled to Missouri.

A fiery summer in Dallas

Shortly after his departure, a general store in Dallas caught fire. Every business in the downtown area was reduced to ashes. In coming days, fires were reported in nearby Denton and several other North Texas communities. The area was in the grip of a terrible drought. The temperature had soared to 110 degrees in Dallas the day of the fire. Historians now speculate that phosphorous matches, newly introduced to the region, spontaneously ignited in the extreme heat.

“Pryor fired off hand-written letters to every pro-slavery newspaper in Texas detailing a ghastly conspiracy.”

But in the eyes of Charles R. Pryor, a Dallas physician who recently had inherited the Dallas Herald, the multiple fires were no coincidence. His printing press having been destroyed in the Dallas inferno, Pryor fired off hand-written letters to every pro-slavery newspaper in Texas detailing a ghastly conspiracy. With each letter he wrote, the scope of the conspiracy grew.

“A LETTER FROM DALLAS,” read the headline in the Houston Telegraph, “A Most Diabolical Plot! Unheard of Scoundrelism!” Pryor blamed the fires on “abolition preachers” who were “actuated by a fiendish malignity of spirit,” and had “returned by stealth, and planned to wreak their vengeance upon the offending communities.”

Within days, Pryor had convinced himself that “emissaries” throughout the state, using vast financial resources provided by “the Abolition Aid Society of the North,” had hatched “a well digested plan, which by fire and assassination will finally render life and property insecure, and the slave by constant rebellion a curse to the master.”

Slaves rounded up and whipped

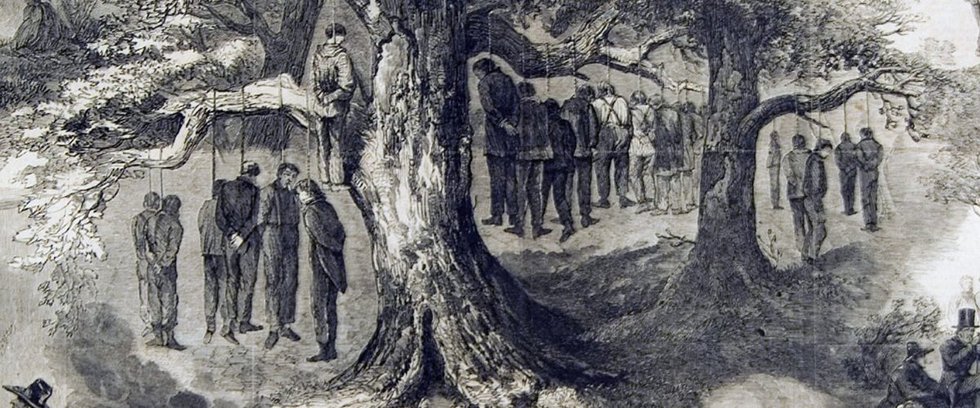

Hanging of the three slaves in Dallas.

Whipped into a frenzy, the Dallas committee of vigilance quickly rounded up 100 Black slaves, whipping them mercilessly until they told the story the committee wanted to hear. Pryor soon was reporting that “the three ring leaders,” Sam Smith, “an old Negro preacher,” and two men identified only by their Christian names, Cato and Patrick, were “escorted from the jail to the place of execution.” Pastor Smith, Pryor reported, had “imbibed most of his villainous principles” from Blunt and McKinney.

Fort Worth citizens gather to observe the body of William Crawford.

A few days later, the body of William H. Crawford, a white resident with abolitionist sympathies, was found suspended from a pecan tree about three-quarters of a mile from Fort Worth. According to Pryor’s report, “a large number of persons visited the body during the day.” A hastily formed committee of vigilance “endorsed the action of the party who hung him.”

Days later, an incriminating letter was found near Bewley’s home. A scheming abolitionist named William H. Bailey discussed the details of a massive plot to spark a slave revolt throughout Texas using poison, arson and assassination. A $1,000 reward was issued for the arrest of Bewley, (more than $30,000 in today’s money), and it wasn’t long before a committee of vigilance in Fayetteville, Ark., located the refugee preacher in Missouri.

Bewley extradited

Bewley was stuffed into a stagecoach under armed guard and turned over to the authorities in Fort Worth. He told the committee of vigilance that he had nothing to say to them. It was clear, he said, that he would be hanged no matter what he said. Before he could have his day in court, a mob broke into the jail, dragged Bewley to the same pecan tree where William H. Crawford had been lynched two weeks earlier, and strung him up. Bewley’s lifeless corpse swung from that tree for two days until slaves were dispatched to cut him down and bury him in a shallow grave.

Ephraim Daggett

A few days later, Bewley’s remains were exhumed, flesh was stripped from bone, and the skeleton was draped on top of Ephraim Daggett’s storehouse where school children were encouraged to play with the bones.

In the next few months, more than 100 persons, Black and white, were connected with Pryor’s conspiracy theory and summarily lynched. On Feb. 2, 1861, Texas threw in its lot with the Confederacy: “a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as Negro slavery — the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits — a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.”

Refusing to sign the declaration, Sam Houston was denounced as a “traitor-knave” and forced to resign the governorship. The following year, with the Confederate Army desperate for conscripts, 41 men in Gainesville, Texas, were hung en masse for refusing conscription into the Confederate Army. In a single day, more than 300 children lost their fathers. It was the largest mass hanging in American history.

What has changed in 160 years?

How much has changed in the 160 years since preaching that Jesus came into world “to set at liberty those who are oppressed” was a hanging offense?

If anything, the conspiracy theories raging in the America of 2020 are more far-fetched than Charles Pryor’s nightmare scenario.

“These fantasy worlds are constructed for, and by, white people.”

Conspiracy theories like QAnon and pandemic-denial are typically associated with a lack of formal education. Bristling with resentment for the coastal elites who are cashing in on the information age, benighted souls come to believe that all their troubles are the work of dark demonic forces.

This analysis makes a lot of sense. If we are talking about white people. But how many uneducated Black people fall into conspiratorial traps such as QAnon, birtherism and the Proud Boys? No more than a handful. No, these fantasy worlds are constructed for, and by, white people. They are a sign of desperation; the last redoubt of white supremacy.

The history of our nation has been disfigured by racial inequity and iniquity. This is not my opinion; it is a fact. And it didn’t happen by accident. It was fully intentional. If white Christian America can’t reckon with this dismal reality, our flight into fantasy can only accelerate.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas. This article is republished with permission from Baptist Global News.

Related articles:

‘The Critique’ versus ‘The Heroic Narrative’ defines the debate in America today | Alan Bean

Church in the Age of Conspiracy Theories |Rhonda Abbott Blevins

Why are Christians so susceptible to conspiracy? | Andrew Gardner

Is QAnon a prophet or provocateur? And how should Christians respond? | Aaron Coyle-Carr