400 years ago, philosopher Blaise Pascal was one of the first to grapple with the role of faith in an age of science and reason

David Hoinski, West Virginia University

In an apostolic letter released on June 19, 2023, Pope Francis praised the “brilliant and inquisitive mind” of the influential French philosopher Blaise Pascal, born on that date 400 years ago.

When Pascal lived, at the height of the 17th century’s scientific revolution, rapid advances were taking place in all areas of science. Pascal’s significant accomplishments included one of the first calculating machines, the world’s first public transport system and various mathematical models, among others.

In fact, Pascal’s influence in the modern world extends so far that biographer James A. Connor wrote, “You cannot walk ten feet in the 21st century without running into something that Pascal did not affect in one way or another.”

I am an expert in the history of Western philosophy. What interests me about Pascal is that he was among the first to grapple with the implications of modern science for religious faith and his scientific sophistication did not keep him from being a devout religious believer.

Religion in the age of science

Pascal was well acquainted with what could and could not be known through the mathematical method, the experimental method and reason itself.

Through his philosophical investigations, he found that there were strict limits to what we as humans could know. For him, neither the scientific method nor reason more generally could teach individuals the meaning of life or the right way to live.

Pascal also wrote about how humans tried to avoid thinking about their mortality, the extent of their ignorance and their liability to error. Yet he also believed that there was nothing more important for people to consider than their true human nature. In this reasoning, without understanding who we are, it would be difficult to understand how we ought to live.

In Pascal’s view, acquiring self-knowledge was a necessary stage on the way to recognizing one’s need for living with faith and purpose in something beyond oneself.

Pascal’s religion

In fact, Pascal argued that believing in the existence of God is essential to human happiness.

For all of his many ideas and accomplishments, he’s probably most famous today for Pascal’s Wager, a philosophical argument that humans should bet on the existence of God. “If you win, you win everything; if you lose, you lose nothing,” he wrote. In other words, he argued, although one cannot know for certain whether or not God exists, we are better off believing in God’s existence than not.

Pascal saw Jesus as the indispensable mediator between God and humankind. He believed that the Catholic Church was the only religion to teach the truth about human nature and therefore offered the singular route to happiness.

Pascal’s preference for Catholicism over any other religion raises a difficult question, however. For why should anyone wager on one religion rather than another? Some scholars, such as Richard Popkin, have gone so far as to call Pascal’s attempts to discredit paganism, Judaism and Islam “pedantic.”

Whatever one’s religious beliefs, Pascal teaches that all individuals have to make a choice between faith in some reality beyond themselves or a life without belief. But a life without belief is also a choice, and in Pascal’s view, a bad bet.

Human beings have to wager and to commit themselves to a worldview on which each one would be willing to bet their life. It follows that, for Pascal, human beings could not avoid hope and fear: hope that their bets will turn out well, fear that they won’t.

Indeed, people make countless daily wagers – going to the grocery store, driving a car, riding the train, among others – but don’t usually think of them as risky. According to Pascal, however, human lives as a whole can also be viewed as wagers.

Our big decisions are risks: For example, in choosing a certain course of education and career or in marrying a certain person, people are betting on a fulfilling life. In Pascal’s view, people choose how to live and what to believe without really knowing whether or not their beliefs and decisions are good ones. We simply don’t and can’t know enough to live without wagering.

Pascal’s unfinished masterpiece

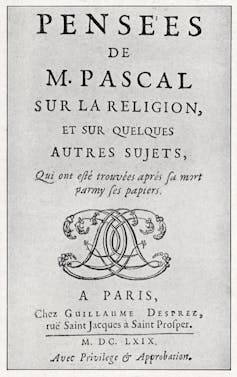

Pascal presents his argument for the wager in his greatest work, the “Pensées” – “Thoughts,” in English. Throughout this work, Pascal emphasizes the need for faith, in light of a multifaceted exploration of human nature as well as a thorough investigation of the limits of reason, science and philosophy.

Pascal’s central argument in “Pensées” for believing in God did not rest on proof of God’s existence. On the contrary, Pascal argued that God’s existence cannot be proved because, for him, God is hidden – a “deus absconditus.” He wrote that “there is enough light for those whose only desire is to see, and enough darkness for those of the opposite disposition,” but ultimately no certainty was possible – and so humans faced a choice.

For Pascal, belief would make the difference between misery and true happiness.

On the 400th anniversary of his birth, then, one way of honoring Pascal might be to risk believing in something beyond ourselves and what we can know; such faith might give us a chance of living well.![]()

David Hoinski, Teaching Associate Professor of Philosophy, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.